A Flock in Focus

Over the wetlands of Senegal, the whirring hum of a drone blends with the rustling calls of pelicans and flamingos. High above the marshes, researcher Alexandre Delplanque operates the aircraft with practiced precision. Below him, an artificial intelligence model silently sifts through the imagery, identifying and counting birds in the dense flocks. A task that once consumed weeks of labor is now reduced to hours.

This is the emerging face of wildlife conservation—one where the power of data meets ecological urgency. Since 1970, global wildlife populations have declined by more than 70 percent. The scale of the biodiversity crisis is staggering. Some scientists argue we are living through Earth’s sixth mass extinction, with habitats shrinking, species vanishing, and time running short. In this context, AI has become more than a tool—it’s a force multiplier for a field long constrained by resources and reach.

Across continents, AI models are being deployed to analyze vast troves of camera trap footage, audio recordings, and aerial imagery when it comes to wildlife conservation. In Panama, one week of AI-analyzed footage yielded more than 300 potential species previously undocumented by science. These breakthroughs hinge on object detection systems built using convolutional neural networks, capable of identifying the presence—or absence—of creatures hiding in plain sight.

Beyond the Canopy

The ecological crisis is not only visible in species loss, but also in the vanishing of the ecosystems they depend on. The United Nations estimates that 10 million hectares of forest are cut down each year—roughly 17 times the size of Los Angeles. The loss of these vital carbon sinks accelerates emissions and wipes out irreplaceable habitats.

Here, too, artificial intelligence is beginning to shift how wildlife conservationists work. Researchers are pairing AI with satellite imagery to detect where deforestation is occurring, often in near real-time. Scottish company Space Intelligence, for instance, has used this technique to map more than 1 million hectares of land across 30 countries. This data is already helping identify illegal logging and guide reforestation efforts.

But the real promise may lie in prevention. By analyzing patterns in land use, infrastructure development, and population density, AI models can predict where deforestation is likely to occur next. These forecasts give governments and wildlife conservation groups the chance to intervene early—placing protections where they’re needed most before the chainsaws arrive.

Still, the digital tools used to protect forests can, ironically, place pressure on the environment elsewhere. Training an advanced AI model often requires immense computing power. While Delplanque’s system—HerdNet—ran on a local machine in under a day, large-scale models used in tech and academia can require thousands of megawatt hours to train. Behind the curtain of progress lies a very physical infrastructure: sprawling data centers, often cooled with billions of gallons of water and powered by fossil-heavy grids.

Environmental researchers are increasingly grappling with the trade-offs. “It’s not about rejecting the technology,” says Laura Pollock, a quantitative ecologist at McGill University. “It’s about ensuring it aligns with our goals—and our limits.”

Speaking for the Silent

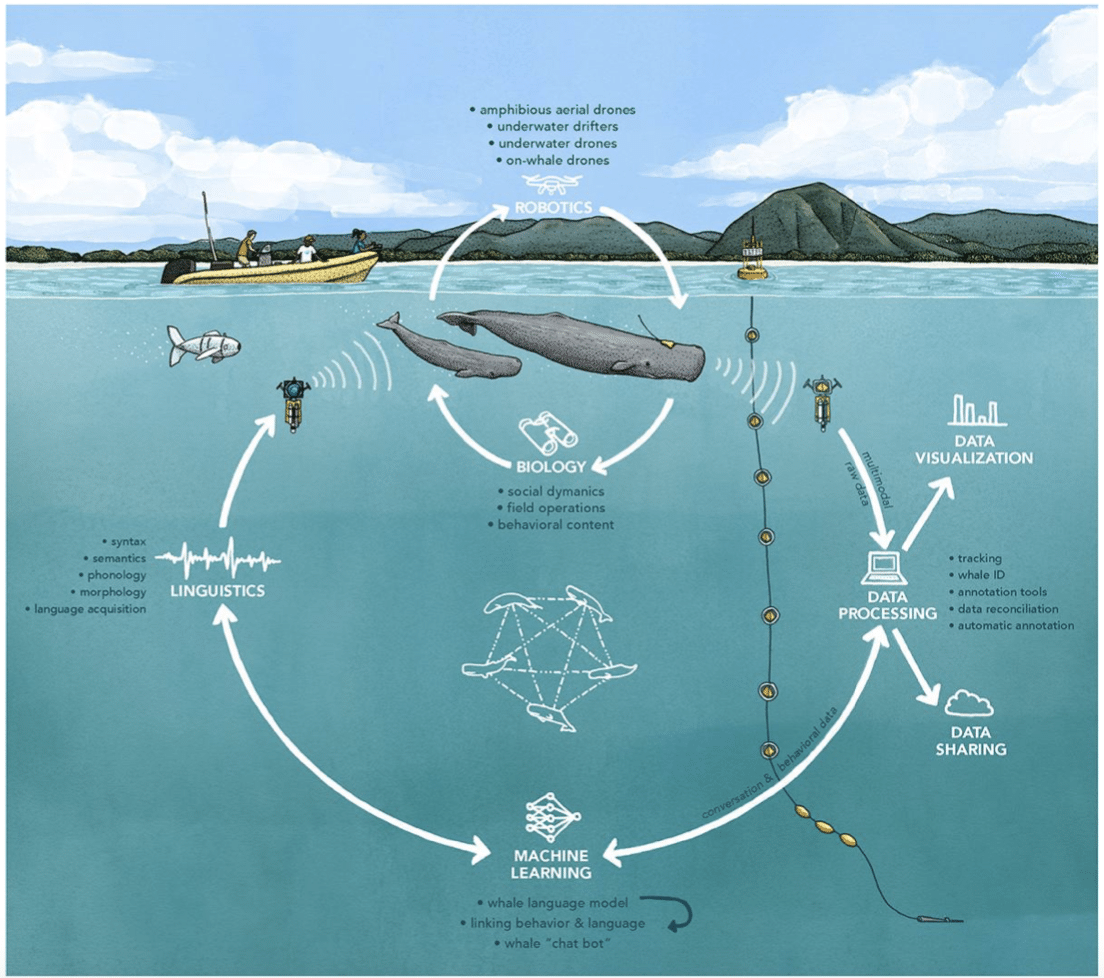

Among the most ambitious—and contentious—uses of AI in wildlife conservation science is an attempt to crack the code of animal communication. Projects like the Earth Species Project and Project CETI are developing models to interpret the vocalizations of elephants and sperm whales, aiming to one day build a human–nonhuman translation system. Researchers have already uncovered hints that elephants might use individual “names” to identify one another.

To some, the idea borders on science fiction. To others, it represents a new frontier in understanding the sentient lives we share the planet with. But the ethical and ecological stakes are high. Do these efforts distract from more urgent wildlife conservation tasks? Are we spending vast resources to chase a poetic—but potentially unattainable—goal?

For Berger-Wolf, the question is not whether such work should be pursued, but how responsibly it’s done. “AI should be used where it can make a meaningful difference,” she said. “If it doesn’t shift the result—if it doesn’t help save a species or a habitat—then it’s hard to justify the cost.”

Project CETI. Image source: Github

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is neither the savior of wildlife conservation nor its saboteur. It is a tool—one with potential to illuminate what was once invisible, to accelerate slow processes, and to uncover new insights in ecosystems under pressure. But it is also a resource-intensive enterprise, one that must be wielded with caution, transparency, and an eye toward unintended consequences.

As the biodiversity crisis deepens and forests fall at an unsustainable rate, the question may not be whether to use AI, but how—and at what cost. The tools are here. What matters now is the wisdom with which we apply them.

You might also like: