Key Takeaways

- Over 90% of marine species remain undiscovered, with roughly 250,000 known species out of an estimated 1–2 million total.

- Researchers now discover approximately 2,000 new marine species per year, a pace accelerated by AI-equipped autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs).

- Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) achieve identification accuracy above 94% for fish species, coral types, plankton, and marine mammals — far surpassing manual methods.

- The Nippon Foundation-Nekton Ocean Census has identified 866 new marine species, using high-resolution imaging, DNA sequencing, and AI-driven data platforms.

- MBARI’s FathomVerse mobile game has engaged 14,000 people across 142 countries to label over 7 million annotations, training AI to recognize deep-sea organisms.

- AI acoustic monitoring identifies cetacean species at up to 97% accuracy through vocalization analysis, enabling passive, non-invasive tracking.

- The global underwater drones market reached $5.1 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $16.7 billion by 2034.

Why the Ocean Remains Biology’s Biggest Blind Spot

The ocean covers 71% of Earth’s surface and holds over 90% of the planet’s habitable space. Yet the species living within it are shockingly underdocumented. At least two-thirds of the world’s marine species are still unidentified. The deep sea — below 200 meters, where sunlight fades entirely — remains Earth’s largest unexplored biome. A widely accepted estimate suggests we have explored only about 20% of the ocean. Every trawl of the deep seafloor returns organisms that have never been catalogued.

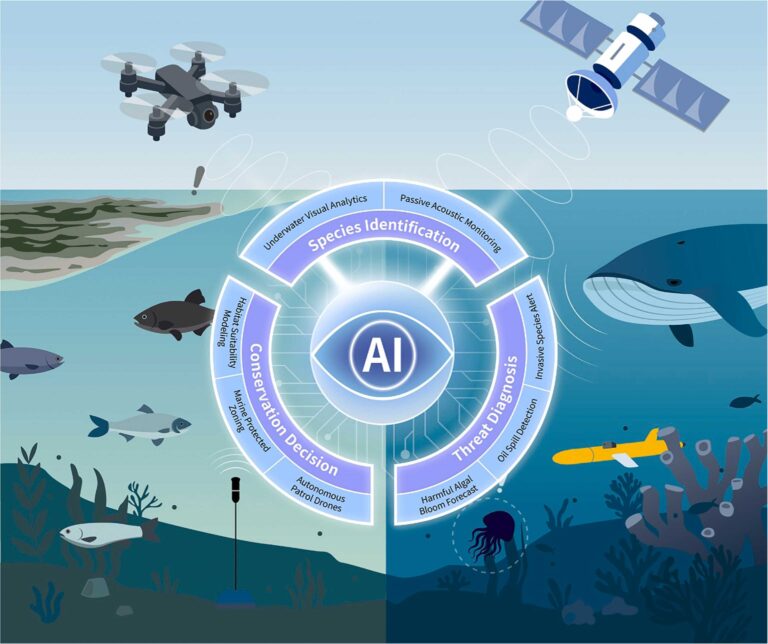

This knowledge gap carries serious consequences. Species that don’t have names don’t get protection. Conservation policies, marine protected area (MPA) boundaries, and biodiversity assessments all depend on knowing what lives where. That is why AI-powered underwater robots and image recognition systems have become some of the most important instruments in modern marine biology. They are turning the ocean from a black box into a searchable database — and doing it faster than any human team ever could.

How AI Identifies Species Beneath the Surface

Computer Vision in Underwater Imaging

The workhorse of AI-driven marine species identification is the convolutional neural network (CNN). Trained on annotated datasets of underwater photographs and video, CNNs detect visual patterns — color gradients, body shapes, fin morphology, texture — that distinguish one species from another. The reference research compiled by Yang et al. (2025) documents dozens of models achieving remarkable precision across wildly different organisms.

| Organism | AI Method | Accuracy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Golden pompano (feeding behavior) | Spatiotemporal attention + LSTM | 97.97% | Zheng et al., 2023 |

| Sea cucumbers | SO-YOLOv5 | 95.47% mAP | Xuan et al., 2023 |

| Microalgae (25 species) | Inception-v3 CNN + transfer learning | >90% | Zhang et al., 2024 |

| Fish species (underwater video) | CrossPooled FishNet (ResNet-50) | 98.03% | Mathur et al., 2020 |

| Whale species | Mask R-CNN + CNN photogrammetry | 98% | Gray et al., 2019 |

| Lake zooplankton | Transfer learning + ensemble methods | 98% | Kyathanahally et al., 2021 |

| Amazonian fish (genus-level) | Computer vision model | 97.9% | Campos et al., 2025 |

| Coral reef 3D mapping | DNN for semantic segmentation | 84.7% mIoU | Zhong et al., 2023 |

| Atlantic salmon (individual ID) | CNN dot localization | 100% (short-term) | Cisar et al., 2021 |

These are not laboratory demonstrations. Automated underwater cameras and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) equipped with these algorithms now run continuously in the field, capturing and classifying imagery in real time. Transfer learning — where a model pre-trained on one dataset adapts to a new environment — has made it practical to deploy CNNs across different marine ecosystems without starting from scratch each time.

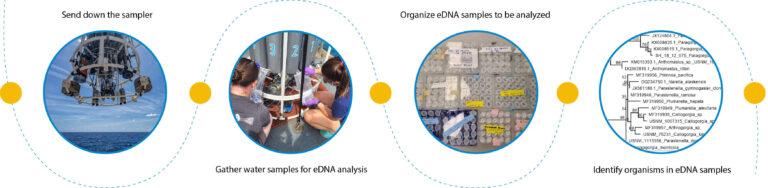

For coral reefs, the gains are especially important. Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, working with NTT Communications, used underwater drones to collect environmental DNA (eDNA) from mesophotic coral ecosystems at depths of 30 to 150 meters — habitats too deep for routine diving — and successfully identified coral genera through metabarcoding analysis. This represents a new frontier: combining robotic sampling with genetic identification to inventory reef biodiversity that was previously invisible.

Acoustic Identification: Listening to the Deep

Not all marine species can be photographed. Many live in perpetual darkness, move too fast, or are too dispersed. For these creatures, sound provides the signal.

AI-enhanced passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) systems analyze underwater soundscapes using CNNs and recurrent neural networks (RNNs). These algorithms parse spectrograms — visual representations of sound frequency over time — to isolate species-specific vocalizations from ambient noise. The technique is especially powerful for cetaceans (whales and dolphins), whose calls carry across vast distances.

| Species | AI Method | Accuracy | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fish species (passive monitoring) | Random forest + SVM | 96.9% | Malfante et al., 2018 |

| Pelagic Mediterranean fish | Two-layer NN + genetic algorithm | 95% | Aronica et al., 2019 |

| Beaked whales | BANTER + random forest | 88–97% | Rankin et al., 2024 |

| Bowhead whale whistles | CNN-LSTM + wavelet transform | 92.85% | Feng et al., 2023 |

| Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins | SVM + spectrogram inspection | 89.9% | Caruso et al., 2020 |

| Bearded seal calls | YOLOv5-based classification | 93.87% | Escobar-Amado et al., 2024 |

| Bottlenose dolphins (individuals) | Signature whistle ID + GAM | Habitat density R² = 0.43 | Bailey et al., 2021 |

These systems now run on autonomous gliders, stationary buoys, and underwater recording units, collecting data across entire ocean basins for months at a time. Beyond species identification, acoustic AI also detects anthropogenic threats — ship noise, industrial activity, seismic surveys — that disrupt marine communication and migration.

The Robots Doing the Work

ROVs and AUVs: Eyes and Ears in the Abyss

The physical platforms carrying AI into the ocean are ROVs (remotely operated vehicles, tethered to surface ships) and AUVs (autonomous underwater vehicles, pre-programmed and untethered). Both categories have matured dramatically.

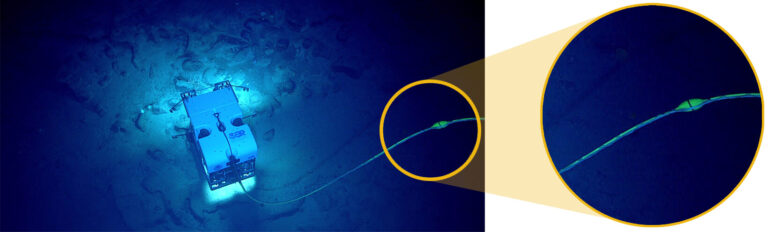

NOAA’s Deep Discoverer (D2), built by the Global Foundation for Ocean Exploration, dives to 6,000 meters carrying 27 LED lights, nine video cameras, hydraulic manipulator arms, suction samplers, and temperature probes. Its companion camera sled, Seirios, absorbs the heaving of the surface ship so D2 can navigate terrain steadily at extreme depth. GFOE has even piloted D2 from shore, reducing the signal lag between joystick command and robot response to just 1.25 seconds — across a satellite relay spanning over 70,000 kilometers.

Junaed Sattar diving with MeCO during a week-long sea trail in the Caribbean Sea. Image credit: Junaed Sattar, University of Minnesota

At the University of Minnesota, NSF-funded researchers are developing MeCO, an open-source AUV platform with modular sensors designed to identify and track invasive species in freshwater lakes. “Our project is about making underwater robots more effective tools for scientists and conservationists. With improved vision and localization, these robots can better understand and protect our underwater environments, which is crucial for ecological balance and human prosperity,” said Junaed Sattar, the project’s principal investigator.

AUVs also carry eDNA samplers — pumping seawater through filters that capture the genetic material organisms shed into the water column. Like forensic evidence at a crime scene, eDNA reveals which species are present without ever seeing or disturbing them. When paired with AI analysis, this method scales species detection across enormous areas.

Remotely operated vehicle Deep Discoverer moves over the seafloor during Dive 08 of the second Voyage to the Ridge 2022 expedition. ROVs communicate with their ship through a long fiber optic cable connecting the ship to the vehicle. Image credit: NOAA

From Footage to Knowledge: The Data Bottleneck

The machines collect data at a pace that humans cannot match by hand. MBARI has amassed an archive of deep-sea video containing more than 10 million observations of animals, behaviors, interactions, and geological features. Manually reviewing this footage requires years of labor by trained taxonomists.

AI offers a solution, but it needs training data first. That is the motivation behind FathomVerse, MBARI’s mobile game. Gamers have generated more than 7 million annotations, reaching community consensus on more than 44,000 previously unlabeled images. These verified labels feed directly into machine learning models that learn to classify marine organisms automatically. The approach merges citizen science with AI development at scale — a strategy that is picking up momentum across the ocean research community.

AI for Ocean Conservation: From Detection to Enforcement

Mapping Threats in Real Time

Identifying species is only the first step. AI also tracks the threats those species face.

Deep learning models now detect harmful algal blooms (HABs) from satellite imagery with up to 99% accuracy (using architectures like ResNeXt50). Predictive models combine satellite data on sea surface temperature, chlorophyll concentration, and meteorological conditions to forecast bloom events before they occur. For coral reefs, AI classifies bleaching severity from hyperspectral imaging, giving reef managers advance warning of stress events. One deep neural network model predicted coral bleaching outcomes with 94.4% accuracy using multi-factor environmental inputs.

Invasive species detection is another active front. Real-time object recognition systems have achieved 98.9% accuracy in identifying invasive fish species for automated removal. In freshwater environments, machine learning classifies aquatic vegetation types from satellite spectral data at over 97% overall accuracy, enabling managers to spot invasive macrophyte spread before it dominates native habitats.

Catching Illegal Fishing With AI

Perhaps the most dramatic application of AI in ocean conservation comes from the fight against illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Dyhia Belhabib, a marine scientist who grew up during Algeria’s civil war, built Spyglass — the world’s largest registry of criminal histories for industrial fishing vessels. She then cofounded Nautical Crime Investigation Services, which uses an AI algorithm called ADA to cross-reference vessel criminal records with real-time movement data.

Her team also built GRACE, an AI risk assessment tool that predicts the likelihood of a specific vessel committing environmental crimes at sea. Combined with automatic information system (AIS) transponder data that tracks ship positions globally, GRACE enables coast guards and agencies like Interpol to prioritize enforcement where it matters most.

Global Fishing Watch, backed by Google and the marine conservation organization Oceana, trains AI algorithms on satellite data to identify vessel types, fishing activity patterns, and gear types. Their analysis has shown that half the global ocean is actively fished, much of it covertly. Researchers have even developed methods to triangulate the positions of vessels running in stealth mode — so-called dark fleets that deliberately disable their transponders.

As Fred Abrahams of Human Rights Watch put it about these satellite-and-AI monitoring systems: “This is why we are so committed to these technologies . . . they make it much harder to hide large-scale abuses.”

In Indonesia, the government shares vessel movement data publicly through Global Fishing Watch, a major step in fisheries transparency. In Ghana, satellite monitoring has helped reduce incursions of industrial trawlers into near-shore waters used by artisanal fishers.

Predicting Climate-Driven Habitat Loss

AI-driven species distribution models (SDMs) combine environmental variables — temperature, salinity, depth, current patterns — with occurrence records to predict where species can survive under different climate scenarios. One study using ensemble modeling (gradient boosting, MaxEnt, random forest) found that six freshwater crab species face losing 70–100% of their current habitat under high-emissions climate projections, while less than 1% of their range is currently protected.

These predictions are essential for designing marine protected areas that will still function as refugia decades from now, as species shift their ranges in response to warming waters.

Traditional Methods vs. AI: Where Each Excels

| Factor | Traditional Methods | AI-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Speed | Slow — weeks to months per survey | Fast — real-time or near real-time |

| Scale | Local to regional | Global, continuous monitoring possible |

| Accuracy | Dependent on observer expertise | CNN models routinely exceed 95% for trained tasks |

| Cost structure | Low upfront, high labor cost over time | High upfront (hardware, training data), low marginal cost |

| Rare species | Prone to missed detections | Improved with data augmentation, but bias toward common species persists |

| Data requirements | Minimal technology | Large annotated datasets, computational infrastructure |

| Adaptability | Immediate expert judgment | Requires retraining for new environments or species |

Neither approach alone is sufficient. AI models still need field-validated ecological knowledge to interpret their outputs correctly. Seasonal changes, water turbidity, shifting light conditions, and tidal dynamics all introduce noise that algorithms must learn to filter. The most effective conservation programs pair automated monitoring with expert review — letting machines handle volume while humans handle nuance.

Challenges That Still Limit AI Underwater

Data scarcity and bias. Most training datasets over-represent common, well-studied species and well-funded regions. Rare or cryptic organisms — often the ones most in need of conservation attention — are underrepresented. The average time from specimen collection to formal species description is 13.5 years, meaning AI models are always working with incomplete taxonomic baselines.

Harsh operating conditions. Underwater environments degrade image quality through turbidity, variable lighting, and particulate matter (“marine snow”). Acoustic signals are warped by temperature gradients and ambient noise. Saltwater corrodes electronics. Pressure at 6,000 meters reaches nearly 600 atmospheres — requiring titanium housings and meticulous engineering.

Communication limits. Radio waves barely penetrate water. AUVs rely on acoustic signals (slow, limited bandwidth) or must surface to transmit data via satellite. Real-time control of deep-water vehicles requires fiber optic tethering, which constrains mobility and range.

Ethical and governance gaps. The same satellite and AI technologies used to track illegal fishing can also be used for migrant surveillance. Belhabib has warned that Digital Earth technologies should prioritize ecological and humanitarian goals over surveillance and profit. Additionally, governance of the high seas — two-thirds of the ocean’s surface — remains weak, though the 2023 UN High Seas Treaty represents progress toward creating enforceable marine protected areas beyond national jurisdiction.

What Comes Next

Several developments are converging to accelerate AI-driven ocean mapping. Environmental DNA analysis, already proven for coral identification, is expanding to full ecosystem inventories collected by AUVs. Explainable AI (XAI) tools are making model outputs more transparent, which builds trust among conservation decision-makers. Open-access biodiversity databases — the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the Ocean Biodiversity Information System, FishBase, and now the Ocean Census Biodiversity Data Platform — are creating shared infrastructure that any research group can use to train better models.

AI can help researchers analyze data more efficiently and scale with the ever-growing amount of visual data, but its value ultimately depends on the quality and diversity of the training data, the willingness of institutions to share it openly, and the integration of computational predictions with ground-truth ecological expertise.

The ocean’s invisible majority — the hundreds of thousands of species we haven’t named — won’t protect itself. The robots, algorithms, and global monitoring networks described here represent the fastest route to cataloguing what’s there before it’s gone.

If you are interested in this topic, we suggest you check our articles:

Sources: MBARI Annual Report, NOAA Ocean Exploration, NSF, MIT Press, H. Yang et al. at ScienceDirect, Ocean Census, Unep-wcmc, The Environmental Literacy Council

Written by Alius Noreika